Altair Insight: Fed Reckoning (4Q22) – Quarterly Market Review

Forgive us if you have heard this before: The Federal Reserve will play the biggest role in determining how financial markets perform this year.

That was the case in 2020, when the Fed joined the Treasury Department in taking emergency action to rescue an economy crippled by the coronavirus pandemic. It was true in 2021, when the Fed stood by as “transitory” inflation fueled by its multitrillion-dollar stimulus began spiraling out of control. And it was the dominating influence again last year, when the Fed led global central banks in raising interest rates at the steepest pace in decades to corral inflation, only to crush markets too.

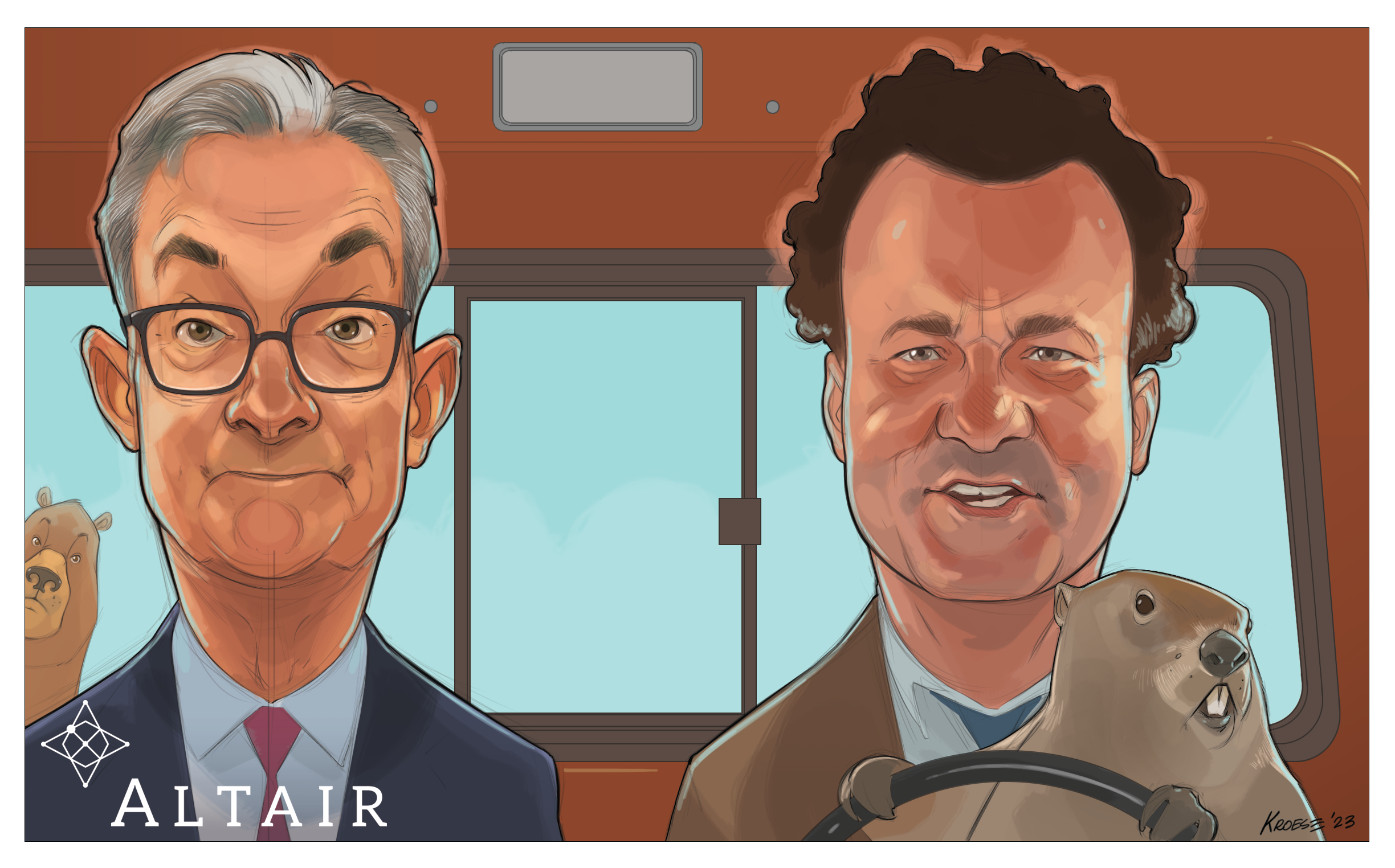

We look forward to the day when Fed action, or inaction, is NOT the determining factor for market performance. But the prospect that the rate-hike campaign will soon end, with uncertain consequences to follow, has once again put the Jerome Powell-led bank front and center for investors as 2023 begins. So we are showcasing Chair Powell in our quarterly cartoon for an eighth consecutive time, for better or worse. Welcome to Groundhog Day, the sequel, featuring the Fed and inflation all over again.

Last year was certainly for the worse. 2022 left nowhere to hide; it was not only the seventh-worst year ever for the S&P 500 but the first in which both stocks and bonds suffered double-digit losses. We expect 2023 – particularly the second half – to be much better, although the first half is likely to be bumpy again as the economy, companies, and investors grapple with the aftershocks from a 4.25% jump (and counting) in the fed funds rate.

The Fed’s actions are hardly all that will shape the economy and markets in 2023, of course.

The global economy faces another tough year with inflation still stubbornly high in much of the world; Russia’s war in Ukraine continues to challenge global trade and energy supplies and risks a deadly further spread; and political brinkmanship over the U.S. debt ceiling could provoke fiscal and market turmoil (although we do not anticipate a default or long-term crisis). On the plus side, the labor market and American consumers remain strikingly resilient despite high inflation and higher interest rates; China’s reopening has the potential to energize the world economy; and the pandemic, while still a threat, continues to wane.

This mix of positive and negative factors keeps our positioning neutral – we are not adding to risk in light of the threats nor are we becoming more defensive, given the opportunities we see and the fact that much of the “bad news” already is reflected in today’s prices.

We are more optimistic about market conditions in the second half of this year, once there is more clarity about the economy. Among the positive harbingers: History bodes well for stock-market performance the year after a major downturn. And the bond market already has stabilized after its worst year ever.

Despite our Groundhog Day theme, then, we expect this year NOT to be a repeat of last year, market-wise. It should be significantly better. What will be a rerun: The influence of the Fed and inflation on markets.

Please read on for more of our thoughts on these and other issues affecting markets:

1. The Federal Reserve is almost done with its steep tightening but will hold rates steady for longer than the markets anticipate. We do not expect rate cuts until at least 2024.

The Fed was wise to slow the pace of its interest-rate increases in December and appears poised to do so again February 1st after raising at a furious pace for much of last year. This shows a needed sense of moderation by the central bank after one of the most aggressive rate-hike cycles in history vaulted the fed funds rate from zero to 4.25% in nine months.

Yet expecting the Fed to reverse course and reduce the rate any time soon seems like wishful thinking to us. We believe the economy will remain sturdy enough to not need a bailout and Fed officials will not blink in their campaign to drive inflation back near 2%.

A halt to rate hikes certainly is in order no later than this spring, given some signs of economic slackening and uncertainty about the full impact of 2022 increases. At issue: “We are just now entering the window where the effects might start to be noticed,” Christina Romer, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley and former chair of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, told a national gathering of economists in January.

We are reasonably confident the Fed will indeed pause within a few months based on officials’ comments and forecasts. According to the most recent “dot plot” of individual Fed members’ projections, the median estimate had the fed funds rate peaking this year at 5.1%. It is nearly there already.

Pushing the rate above that level could put economic growth in jeopardy. The Fed already is blamed for causing a significant number of the 13 U.S. recessions since World War II by tightening monetary policy rapidly. It has a chance to avoid a recession, or at least a severe one, by not overtightening this time. A rate of 5% or a bit more, while relatively lofty by historical standards, would not be oppressive. U.S. companies have sufficient fundamental strength to adjust to it.

Why not ease the pressure on the economy by reducing rates later this year? A majority of market traders expect the Fed to do just that, according to the CME FedWatch Tool. We are skeptical. The only reason policymakers would do that in 2023, in our view, is if the economy falls into a serious recession or inflation falls off a cliff – neither of which is likely.

Fed officials pride themselves on being data-dependent and willing to revise their positions as economic winds shift. But since their belated start in raising rates they have been unswerving in their mission to stamp out high inflation and return it to the 2% level, which is considered unlikely to be reached until 2024 or 2025. All but two of 19 Fed members recently predicted a rate of 5% or higher by year-end. We would not “fight the Fed” and expect otherwise.

Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly emphasized that history warns against prematurely loosening policy. He is emphatic that the Fed will not consider backing away from its 2% inflation target “under any circumstances.” But this is not just Powell’s crusade. Even some Fed members known previously for advocating a more lenient monetary policy are sounding consistently hawkish about the need to extend the inflation crackdown. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said the Fed needs to raise its policy rate above 5% and hold it there. Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic, asked in January how long he sees the rate staying above 5%, responded: “Three words: a long time.” Minneapolis Fed President Neel Kashkari, a voting member, said the Fed is obligated to get inflation down to 2% and “not just come up short because it is too painful to get there.”

The Fed has another reason to put off a rate cut, too. Even with inflation having turned a corner, it wants to see cooling in the labor market in order to keep inflation sustainably lower. Powell fears that a job market that still has nearly two openings for every unemployed person risks driving up wages and business costs at a pace that causes high inflation to stick around.

Keeping rates steady at near current levels this year would not necessarily bode poorly for markets. It would mean the economy has avoided falling into a hole so deep the Fed has to rescue it again by loosening its restrictive policy. We view that scenario – a severe recession – as unlikely.

2. Inflation’s consistent decline makes it less of a headwind for markets. We expect it to drop substantially by year-end but not down to the 2% target.

Inflation is not coming down quite as rapidly as it rose in 2022. The steady pace of descent, however, is a positive sign even with some likely obstacles looming ahead.

The most recent economic reports provide more evidence that the worst inflation shock since the early 1980s, while not over, is fading. The Fed’s anti-inflation campaign has succeeded in nudging the year-over-year change in the Consumer Price Index down to 6.5% in December from 9.1% last June and lowering the closely watched core PCE (personal consumption expenditures) index to 4.7%. The deceleration helps reduce the economic damage from the Fed’s tardiness in tackling inflation until it was approaching a 40-year high. In Europe, which has experienced even worse inflation, a similar decline in December also boosted hopes that the peak has passed.

The sharp drop in energy prices, which started rising after the world reopened from pandemic lockdowns and soared when Russia invaded Ukraine a year ago, has been a key factor in the decline. Even excluding energy and food, however, three straight months of relatively lighter core inflation show that U.S. price increases are slowing across many categories. Inflation has even reversed course in an area that badly overheated in 2022: Used-car prices have fallen 8.8% below year-ago levels.

The service sector, where price increases have remained stubbornly high even as goods inflation recedes, is a notable exception. Core services prices were up 7% in December from a year earlier, climbing from 6.8% in November. But an important leading indicator for inflation that has yet to be reflected in the official number – shelter, which makes up 33% of CPI – points to improvement soon. The price of new housing rentals has been decelerating for months, according to Zillow, and it can take a year for those numbers to flow through to the Labor Department data. That lagged effect of slower housing cost growth should help the CPI show progress in the months ahead.

Despite all the cooling, inflation remains near a multi-decade high and still is a challenge to the economy and markets. The same resilient consumer demand that has buttressed growth during the slowdown, coupled with above-average wage increases, will keep upward pressure on prices. Inflation expectations, which can sometimes become self-fulfilling, remain elevated: Consumers anticipate 4.6% inflation in the coming year, according to the University of Michigan.

Several other factors pose potential inflation traps by reigniting spending. Among them: the new $1.7 trillion U.S. government funding law, China’s reopening after a long period of isolation, and geopolitical tensions fueling global weapons spending.

We believe inflation will continue trending down from last year’s peak. The deceleration path from here is unlikely to be linear, however, and it faces some potential stumbling blocks in the months ahead. The Fed’s 2% target has gotten closer, but we do not expect it to be reached in 2023.

3. The economy is slowing but is on a clear path to avoid a severe recession, and perhaps a recession altogether, thanks to the strong labor market and consumer.

Jerome Powell’s initial suggestion last May that the U.S. economy had a good chance for a “soft or softish landing” raised eyebrows on Wall Street. With the Fed just starting to fight inflation with its most drastic policy tightening in decades, it was “a big ask,” as one strategist called it.

As 2023 begins, we view Powell’s scenario as increasingly plausible. A soft landing, defined by Investopedia as a cyclical slowdown in economic growth that avoids recession, is hardly assured; we believe the odds of a mild recession in the next 12 to 18 months remain substantial. But the economy’s ability to withstand the Fed’s punches and remain not just standing but growing after months of rate increases reinforces our belief that no deep recession is likely.

The global outlook is murky, with Europe and some other regions also facing a strong possibility of recession. The World Bank in January lowered its growth forecast for the world economy in 2023 to 1.7% in the face of persistently high inflation and the war in Ukraine. That would signify the third-weakest pace of global growth of the 21st century after the 2009 and 2020 downturns.

Perhaps the biggest wild card is the unknown impact of China’s abrupt reopening in January after ending its draconian zero-Covid policy following three years of self-imposed isolation. The ability of the world’s second-largest economy to endure a huge wave of coronavirus infections and pull out of a slump is the single most important factor for global growth in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund. Another is the resilience of the U.S. labor market, says Kristalina Georgieva, the IMF’s managing director.

Overall, U.S. economic data are mixed and weakening. The Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index, a composite of 10 key indicators, has fallen for 10 consecutive months. The housing market is steadily deteriorating. A barometer of business conditions at service-oriented companies, the U.S. Services PMI (purchasing managers index), turned negative in December for the first time since May 2020. The manufacturing industry gauge declined to its lowest since April 2020.

Two strong categories, however, have enabled the economy to ride out a slowdown in pretty good shape: a buoyant job market and strong consumer demand.

Job growth slowed by more than half in 2022 but the monthly rate of 247,000 in the fourth quarter was still strong. Job openings remain elevated at 10.5 million, or 1.8 for every unemployed person, with the jobless rate just 3.5%. This suggests the labor market may be running too strong for the Fed’s liking but highlights that economic conditions are firm. Consumers’ excess savings that accumulated during the pandemic, boosted by government fiscal stimulus payments, have been dwindling but remain elevated. Consumer spending likewise has slowed in the face of inflation but remains brisk by historical standards.

Corporate earnings are likely to see some deterioration, starting with guidance issued during the current reporting season. In the meantime, the economic picture we see is hardly recessionary.

4. We think 2023 will be a positive year for markets despite the challenges with corporate earnings and other risks.

The worst global inflation in decades was the primary catalyst for stocks’ plunge in 2022. Now that price increases have been slowing in the United States and elsewhere, there are legitimate prospects for markets to regain their balance and erase at least some of last year’s painful losses. Significant hurdles to a recovery remain, however, causing us to maintain our neutral positioning in the three risk categories: higher risk, medium risk and lower risk.

First, the hurdles, which make for a challenging outlook for the first half of 2023 in particular.

Now that inflation is trending lower, we believe corporate earnings will increasingly become the biggest concern of the year. Fourth-quarter reporting season, under way as we write, should provide a clearer picture of the challenges facing companies. As of late January, analysts were forecasting the first decline since 2020 in the fourth quarter (-3.9%) and also had switched their estimates for the first and second quarters of 2023 from growth to year-over-year drops.

The strength of the U.S. economy, still by far the world’s largest despite China’s heralded growth, is key to any rebound. Markets appear to have built expectations for at least a mild recession into current prices with last year’s pullback. But higher rates than currently anticipated or a sharp recession – not our base case – would likely cause more damage.

Given that interest-rate cuts take months to work their way through the system, the next few months will tell us a lot about the economy’s resilience. And the federal debt-ceiling showdown that seems almost inevitable because of the tense relations and razor-thin majority for Republicans in the House risks causing a protracted disruption. Ultimately, we expect Congress and the federal government to find a way through the emergency without a U.S. default, but not without short-term market turmoil.

Globally, China’s reopening carries meaningful near-term risks for the worldwide economy and poses a threat to markets because of the potential impact on inflation. So does Russia’s war in Ukraine as it nears the one-year mark with no resolution in sight.

Yet, other factors appear to suggest a market recovery occurring sooner rather than later.

The decline in inflation at the end of 2022 and into this year is encouraging, particularly if central banks adopt less austere monetary policies this year as a result. The U.S. economy has remained robust. Forward returns look more promising as a result of the market’s retrenchment. The S&P 500 began the year fairly valued with a trailing price-earnings ratio of 19.4 – below both the five-year (22.7) and 10-year (20.6) averages.

And while past performance should not be used topredict future returns, several historical trends appear favorable for stocks in the wake of last year’s sell-off.

Consecutive down years for stocks are rare. Back-to-back years of negative returns have occurred only eight times in the S&P 500 Index’s nearly century-long existence. Negative years for both stocks and bonds are even rarer, occurring only twice in the past 50 years, and stocks were sharply higher the following year both times.

The U.S. bear market – defined as a drop of 20% or more in the S&P 500 – that began on January 3rd a year ago is already longer than the average post-WWII bear.

Not insignificantly, too, the plunge that took the benchmark down as much as 25% at its low point in October, has taken much speculative excess out of the markets, particularly in some tech stocks.

The first half of 2023 will test markets as the economy slows and the Fed decides how restrictive its policy should be. However, we believe markets are well positioned to rebound later this year if the Fed stops its increases before risking more than a mild recession.

5. After the bond market debacle in 2022, yields are normalizing to levels not seen in years and bond holders are being compensated well again.

It would be hard to exaggerate how much an outlier year 2022 was for bonds. The historical benchmark for taxable bonds, the Bloomberg Aggregate Bond Market Index, previously had only four down years since its inception in 1976. The worst was 1994, when it fell 2.9%. Last year’s drop was fourfold compared with that: 13.0%. And the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond was down more than 15% in 2022, its largest negative return and just the second since the 1920s (the other was an 11.1% loss in 2009).

Instead of providing their usual safe haven and acting as a portfolio diversifier for investors, bonds fell along with stocks in 2022.

Bonds’ rout might in retrospect seem to have been inevitable in a year when the Federal Reserve undertook its fastest and most aggressive tightening cycle since the 1980s. But the rapidity and size of the moves caught the markets flatfooted. At the start of the year, the Fed did not anticipate inflation reaching 40-year highs by last summer and had no idea of the extent of rate hikes that would be needed to tamp it down. The consensus view of markets and the Fed itself was for two to three quarter-point increases in 2022, with a “worst case” of a 1% federal funds rate. Instead, the Fed raised the rate from zero to 4.25% by year-end.

Small additional rate increases are likely at the Fed’s February and March meetings, and more could follow if the central bank is not satisfied that the economy has sufficiently cooled. But bonds stopped their slide in the fourth quarter as the 10-year Treasury yield finally declined after topping 4.2%. We expect them to produce gains this year, especially once the Fed pauses and/or reaches the top of its tightening cycle. An additional two or three increases are already priced into yields.

Investors now have opportunities to earn significant income without having to take on much or any credit risk. Bonds today are trading almost at a discount across the board. Many companies’ earnings could weaken, but unlikely to a level where they would be unable to pay their debt obligations, which benefits bondholders.

We still are not overweighting bonds because of the risk that rates go higher than expected as well as a still-inverted yield curve (where short-term rates are higher than long-term rates). Overall, however, it is a better time to be a bond investor again. One abnormally terrible year does not invalidate decades of evidence that they can effectively diversify portfolios and cushion the risks of stocks.

Our Outlook

- The Federal Reserve is likely to keep its benchmark interest rate elevated throughout the year and forgo a cut until 2024. The Fed has been unwaveringly explicit for months about its intention to force inflation back to its 2% target and a resilient economy will enable it to hold to that goal.

- Inflation has peaked and will continue to trend lower in 2023, although the decline may not be as consistent as in recent months. China’s reopening, rapid U.S. wage growth and the record $1.7 trillion government funding law could slow its downward progress by stimulating higher spending.

- Slowing growth will make this another challenging year for the world economy, particularly with central banks still raising interest rates. However, the U.S. economy has held up well under duress and likely faces no worse than a mild recession even as the full impact of nearly a year of rate hikes is felt.

- Stocks face the likelihood of more turbulence in 2023 but should be well-positioned to rebound later in the year. The extent of the recovery will depend on the pace of inflation and the Fed’s tightening.

- The carnage in bonds has allowed for a reset with higher yields across all maturities. Currently we find short-maturity Treasurys to be compelling on a risk-adjusted basis. Bonds have resumed their key role in portfolios as diversifiers by reducing volatility, generating income and providing liquidity.

- Geopolitical risks that include authoritarian threats from Russia, China and Iran pose potential challenges to global stability. They are offset for now by the pandemic’s weakened clout, Russia’s failing war in Ukraine, and the economic strength and resilience of the United States, Europe and the G7.

Quotes of the Quarter

“If that resilience of the labor market in the U.S. holds, the U.S. would help the world to get through a very difficult year.” – Kristalina Georgieva, International Monetary Fund managing director

“Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth and some softening of labor market conditions.” – Jerome Powell, Federal Reserve chair

“Policy will need to be sufficiently restrictive for some time to make sure inflation returns to 2% on a sustained basis. We are determined to stay the course.” – Lael Brainard, Federal Reserve vice chair

Market Data

U.S. Stocks

Much-improved performance by U.S. stocks in the final quarter could not nearly offset the cumulative toll of elevated inflation, higher interest rates and the war in Ukraine in 2022. The iShares S&P 500 ETF finished with a negative total return of 18.1% for the year even with a 7.6% gain in the last three months. It was the biggest annual loss for the index in 14 years and fourth-worst since its inception in 1957. The only worse years for large-cap stocks were 2002, 1974 and 2008.

Every stock sector but consumer discretionary produced gains in the fourth quarter, but the only positive total returns for the year came from energy (a record 64% total return because of the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on oil and gas supplies) and utilities (1.5%). The most impactful loser of 2022 was technology, down 27.7% for the year, which accounted for approximately 44% of the index’s decline. Former high fliers Meta, Apple, Netflix and Alphabet sent the once-dominant FAANG group of tech giants crashing by a collective 40%. Growth stocks underperformed value in the quarter and for the year as a result of rising rates and subsequently weaker economic growth.

Small caps also staged a fourth-quarter rally on investors’ return to risk. The comeback ended abruptly in December, as with large caps, but lifted the benchmark iShares Russell 2000 ETF by 6.2% over the final three months and trimmed its full-year loss to 20.4%.

International Stocks

The dollar’s 7% drop against other leading currencies spurred an exceptional rebound by overseas stocks to close out an otherwise abysmal year, enabling them to outperform their U.S. peers for the year for the first time since 2012. The iShares MSCI EAFE ETF, proxy for developed international markets, surged 17.7% to improve its full-year return to negative 14.1% after having plummeted 27% through nine months. Before the benefit of dollar conversion, it was up much less in local currencies in the fourth quarter: 8.8%.

The dollar previously was on a historic rally, surging 18% from the start of 2022 to its peak in late September due to the Fed’s steep interest-rate hikes and the U.S. economy’s superior strength. But the Fed’s stance turned less hawkish late in the year and central banks in Europe and Japan raised rates more aggressively to close the gap with higher U.S. yields. That drove up other currencies against the greenback and reduced conversion costs for foreign investments held in dollars. The trend also boosted emerging-markets stocks; the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF rose 10.3% in paring its 2022 loss to 20.5%.

Many foreign markets saw double-digit declines for the year as a result of war, inflation and tightening monetary policy. Dollar-based stock investments in China (-27.4%) and Germany (-21.8%) fared worse than U.S. stocks. But Brazil (+12.1%), Mexico (+1.4%), the United Kingdom (-4.2%), France (-11.7%) and Japan (-17.5%) were among the majority that outperformed the U.S. market.

Real Estate

Publicly traded real estate investment trusts managed their first positive quarterly returns of 2022, bouncing back after consecutive double-digit losses as the Fed moved closer to completion of its rate-hike cycle. The Vanguard REIT Index Fund, comprised of U.S. stocks issued by commercial REITs, underperformed the broad stock market for a second consecutive quarter but logged a 4.3% gain to lower its 2022 loss to 26.2%. Internationally, the Vanguard Global ex-US Real Estate ETF rebounded 9.8% to surpass its U.S. peer for the year with a negative 22.4% return.

Hedged/Opportunistic

Publicly traded senior bank loans, as well as private debt (direct lending), continued to outperform most other sectors in fixed income as was the case throughout 2022. These loans generally have floating interest rates that are less impacted when the Fed raises short-term interest rates. The Invesco Senior Bank Loan ETF produced a 3.7% return and was down only 2.5% for 2022. Direct lending held up even better due to higher yields and low default rates.

Fixed Income

Inflation, rate hikes and the turbo-charged dollar reduced bonds’ appeal to investors for much of 2022. While the historic rout in bond prices ended in September, a solid rise from there to year-end left benchmarks far short of break-even territory for the year. The Fed’s rapid rate hikes throughout the year to combat inflation were matched by a sharp rise in the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield from 1.5% to 3.9%, causing prices of bonds already in the market to plummet.

It was the worst year on record for U.S. bonds as gauged by the Bloomberg Aggregate U.S. Bond Index, which dropped by 13% after never previously having fallen by more than 2.9% (1994). The similar Vanguard Total Bond Market ETF, Altair’s preferred benchmark for taxable-bond investments, finished 2022 down 13.1% after a 1.6% upturn in the fourth quarter.

The tax-exempt municipal bond market also recovered in the final months of 2022 as tax-exempt yields fell and demand for munis surged. Altair’s benchmark for tax-exempt munis, a blend of the Market Vectors short and intermediate ETFs, climbed back 3.2% in the final quarter to end the year with a negative 6.2% return.

The material shown is for informational purposes only. Past performance is not indicative of future performance, and all investments are subject to the risk of loss. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties, and actual results may differ materially from those anticipated in forward-looking statements. As a practical matter, no entity is able to accurately and consistently predict future market activities. Information presented herein incorporate Altair Advisers’ opinions as of the date of this publication, is subject to change without notice and should not be considered as a solicitation to buy or sell any security. While efforts are made to ensure information contained herein is accurate, Altair Advisers cannot guarantee the accuracy of all such information presented. Material contained in this publication should not be construed as accounting, legal, or tax advice. See Altair Advisers’ Form ADV Part 2A and Form CRS at https://altairadvisers.com/disclosures/ for additional information about Altair Advisers’ business practices and conflicts identified. All registered investment advisers are subject to the same fiduciary duty as Altair Advisers.

ETFs and mutual funds selected by Altair are intended to approximate the performance of the respective asset class in lieu of an established index. An ETF or mutual fund is generally managed by an adviser and, therefore, can be subject to human judgment while an index is typically comprised of an unmanaged basket of instruments designed to measure the performance attributes of a specific investment category. Unlike indices, the ETFs and mutual funds selected incorporate fees into their performance calculations. There can be no assurance that an ETF or mutual fund will yield the same result as an index. Altair has no relationship with the ETFs and mutual funds selected.

Any blended benchmark referenced is comprised of a collection of indices determined by Altair Advisers. Altair Advisers used its judgement to select the indices and relative weightings to be shown, with the objective of providing the user with a meaningful benchmark against which to compare performance. Despite its best efforts to remain neutral in selecting the indices and their relative weightings, the blended benchmark should not be viewed as bias-free as elements of human nature inherently played a role in selecting the components of the blended benchmark.

The Closed-End Fund Blended Benchmark consists of 60% First Trust Equity Closed-End Fund TR USD Index, 20% Invesco CEF Income Composite ETF, and 20% VanEck Vectors CEF Municipal Income ETF.

The Securitized Credit Benchmark consists of 65% iShares MBS ETF and 35% iShares iBoxx $ High Yield Corporate Bond ETF.

The U.S. Municipal Bonds Benchmark consists of 65% VanEck Short Muni ETF and 35% VanEck Intermediate Muni ETF.

© Altair Advisers LLC. All Rights Reserved.